List of Greek deities

Deities in ancient Greece were seen as immortal, anthropomorphic, and powerful.[2] They were conceived of as individual persons, rather than abstract concepts or ideas,[3] and were described as being similar to humans in appearance, though they were considered larger and more beautiful.[4] Though typically found in mythology and religion in an anthropomorphic visage, the gods were also capable of taking on the form of various animals.[5] The emotions and actions of deities were largely the same as those of humans;[6] they frequently engaged in sexual activity,[7] and were fickle and amoral.[8] Deities were considered far more knowledgeable than humans,[9] and it was believed that they conversed in a language of their own.[10] Their immortality, the most defining marker of their divinity,[2] meant that, after having grown to a certain point, they did not age any further.[12] In place of blood, their veins flowed with ichor, a substance which was a product of their diet,[13] and conferred upon them their immortality.[14] Divine power allowed the gods to intervene in mortal affairs in various ways; they could cause natural events such as rain, wind, the growing of crops, or epidemics, and were able to dictate the outcomes of complex human events, such as battles or political situations.[15]

Ancient Greek religion was polytheistic,[16] and a multiplicity of gods were venerated by the same groups and individuals.[17] The identity of a deity is demarcated primarily by their name, though this name can also be accompanied by an epithet (or surname),[18] which may refer to a specific function of the god, to an association with another deity, or to a local form of the divinity.[19] Worship was the means by which the Greeks honoured their gods, as they believed deities had the power to bring to their lives various positive outcomes which were beyond their own control.[20] Greek cult, or religious practice, consisted of activities such sacrifices, prayers, libations, festivals, and the building of temples.[21] By the 8th century BC, most deities were honoured in sanctuaries (temenē), sacred areas which often included a temple and dining room,[22] and which were typically dedicated to a single deity.[23] The cult a of deity contributed to how they were viewed, based upon the kinds of sacrifices made in their honour, the relation of their rituals to the social order, and the location of their sanctuaries.[24]

In addition to their name and cult, a god's character was determined by their mythology (the collection of stories told about them), and their iconography (how they were depicted in ancient Greek art).[25] Mythological stories about a deity told of their deeds (which may have related to their functions) and linked them, through genealogical connections, to other gods with similar functions.[18] The most important surviving accounts of Greek mythology can be found in Homeric epic, which tells of encounters between gods and mortals, and Hesiod's Theogony, which explicates a genealogy of the gods.[26] Some myths attempted to explain the origins of certain cult practices,[27] while others may have arisen from rituals;[28] myths known throughout Greece can also have differing local versions.[29] Artistic representations allow us to understand how deities were depicted over time from the early archaic period, and works such as vase paintings can significantly predate literary sources.[30] Art contributed to how the Greeks conceived of the gods, and depictions would often assign them certain symbols, such as the thunderbolt of Zeus or the trident of Poseidon.[18]

The principal gods of the Greek pantheon were the twelve Olympians,[31] who lived on Mount Olympus,[32] and were connected to each other as part of a single family.[33] Zeus was the chief god of the pantheon, though Athena and Apollo were honoured in a greater number of sanctuaries in major cities, and Dionysus is the deity who has received the most attention from modern scholars.[34] Beyond the central divinities of the pantheon, the Greek gods were numerous.[35] Some parts of the natural world, such as the earth, sea, or sun, were held as divine throughout Greece, though other natural deities, such the various nymphs and river gods, were primarily of local significance.[36] Personifications of abstract concepts appeared frequently in Greek art and poetry,[37] though many were also venerated in cult, with some being worshipped as early as the 6th century BC.[38] Groups or societies of deities could be purely mythological in importance, such as the Titans, or they could be the subject of significant worship, such as the Muses or Charites.[39]

Major deities in Greek religion

The following section is structured after Walter Burkert's Greek Religion, particularly his section "Chapter III: The Gods".[40]

Twelve Olympians

| Name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Aphrodite Ἀφροδίτη |

|

Goddess of sexual love and beauty.[41] In Hesiod's Theogony she is born from the castrated genitals of Uranus, while in the Iliad she is the child of Zeus and Dione.[42] She was worshipped throughout the Hellenic world, and her best-known cults were located on the island of Cyprus.[43] A number of scholars believe she was Near-Eastern in origin, though others argue she was derived from a Cypriot goddess who contained indigenous elements.[44] In the Odyssey, she is married to Hephaestus, though she fornicates with Ares, and the two are caught in sexual embrace by an invisible net crafted by her husband.[45] She also had affairs with mortals such as Adonis and Anchises, and would provide help to mortal lovers while punishing those who spurned love.[46] In art, she was represented from the 7th century BC as a robed figure, though in the Hellenistic period various nude and semi-nude depictions were produced;[47] among her symbols were various birds, especially doves.[48] Her Roman counterpart is Venus.[49] |

| Apollo Ἀπόλλων |

|

Son of Zeus and Leto, and twin brother of Artemis.[50] His various functions and associations include healing, music, archery and prophecy,[51] and he has often been characterised as the "most Greek" of the gods.[52] Apollo's cult existed throughout Greece, having been this widespread by the beginning of the 7th century BC,[53] and was likely been brought to Greece during the Greek Dark Ages.[54] By the 5th century BC, his worship had been introduced into Rome, where he was revered primarily as a god of healing.[55] In mythology, he was said to have slain the dragon Python, who guarded an oracle of Themis at Delphi, before taking over the shrine for himself.[56] He had numerous love affairs with nymphs and women such as Daphne and Cyrene, as well as with males such as Hyacinth,[57] though he was often unsuccessful in his amorous pursuits.[58] In art, he is depicted as a youth, usually without a beard,[59] and can be found portrayed as a lyre player or archer.[60] From the 5th century BC, he was often equated with the sun.[61] |

| Ares Ἄρης |

|

God of war.[62] He is the son of Zeus and Hera,[63] and the lover of Aphrodite,[64] by whom, in the Theogony, he is the father of Deimos, Phobos and Harmonia.[65] His cult was relatively limited,[66] and his temples were located mostly on Crete and in the Peloponnese;[67] he also often appeared alongside Aphrodite in cult.[68] In the Iliad, he is depicted in a largely negative manner, as a brash and wild warrior;[67] he supports the Trojan side of the war, and is frequently presented in opposition to Athena.[69] In ancient art, he was depicted early on as a warrior, bearded and with a spear and shield, though from the classical period he can found as a beardless and more youthful figure.[70] In Rome, his counterpart was Mars.[71] |

| Artemis Ἄρτεμις |

|

Daughter of Zeus and Leto, and twin sister of Apollo.[72] She presided over transitions,[73] and was associated with hunting and the wild.[74] Her cult was the most far-reaching of any goddess,[75] and she presided over female (as well as male) initiation rites.[76] She is among the oldest of the Greek gods, and is closely linked with Asia Minor.[77] In Homeric epic, she is described as a talented hunter who traverses the Arcadian mountains, accompanied by a retinue of nymphs.[78] She remained a young maiden and virgin indefinitely,[79] and men who attempted to violate her chastity generally faced severe consequences.[80] She dispatches swift punishment against mortals who display arrogance towards her, or fail to honour her properly,[81] and is also known for unexpectedly and suddenly killing mortal women.[82] In art, she is often depicted as a hunter carrying a bow and arrow, and wearing a dress, though from the 7th century BC there exist depictions of her as Potnia Theron.[83] Her Roman counterpart is Diana.[80] |

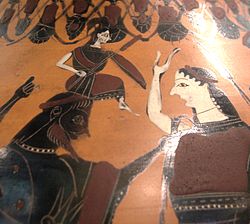

| Athena Ἀθηνᾶ |

|

Daughter of Zeus, who is born from his head after he swallows her mother, Metis.[84] She was originally a Minoan or Mycenaean goddess, and her name is likely derived from that of Athens.[85] Throughout Greece she was the foremost polis deity, and in Greek cities her temple was typically located on the citadel;[86] the nexus of her worship was the Athenian Acropolis, upon which there was temple to her by the 8th or 7th century BC.[87] She is both a virgin goddess and a warrior,[88] and is the patroness of all forms of craftmanship.[89] In mythology, she competes with Poseidon for the patronage of Athens, besting him by offering its inhabitants the olive tree.[90] She is described as a provider of aid to male heroes,[91] helping figures such as Heracles, Perseus, and Bellerophon in their quests.[92] In the earliest known artistic depictions of Athena, she wears a helmet and carries a spear and lance, and around the early 6th century BC there begin appearing representations including the aegis and a shield adorned with a gorgoneion.[93] Her Roman counterpart is Minerva.[94] |

| Demeter Δημήτηρ |

|

Goddess of agriculture.[95] She is the daughter of Cronus and Rhea, and the mother of Persephone by Zeus.[96] She and her daughter were intimately connected in cult,[97] and the two goddesses were honoured in the Thesmophoria festival, which included only women.[98] Demeter presided over the growing of grain, and she was responsible for the lives of married women.[99] Her most important myth is that of her daughter's abduction, in which Persephone is stolen by Hades and taken into the underworld;[100] hearing the cries of her daughter as she is taken, Demeter traverses the earth looking for her, and local versions of the story tell of her interactions with mortals during her search.[101] This myth, which is first narrated in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter,[102] was central to the Eleusinian Mysteries,[98] the most ancient of the Greek mystery religions.[103] In art, Demeter is typically depicted as a clothed figure, and features of her representations include the polos, calathus, sheaf, and torch.[104] Her Roman counterpart is Ceres.[105] |

| Dionysus Διόνυσος |

|

Son of Zeus and the mortal woman Semele.[106] He is the "most versatile and elusive" Greek deity,[107] and is the god who has received the greatest attention in modern scholarship.[108] He is the god of wine, intoxication, and ecstasy,[109] and is associated with theatre, eroticism, masks, and madness.[110] His name is attested in Mycenaean Greece,[111] and there is evidence of him having been worshipped continuously from the 15th century BC.[112] His cult was more far-reaching than that of any other Greek god;[113] his festivals, which could be found across the Greek world, often featured drunkenness and revelry,[114] and included the Anthesteria, the Agrionia, the Rural Dionysia, and the City Dionysia.[115] His pregnant mother dies upon seeing Zeus in the form in which he appears to Hera, and Zeus stitches the unborn god into his thigh, from which he is then born.[116] He is accompanied by a retinue of satyrs, maenads, and silenoi, and is said to have travelled with his followers to locations such as Egypt and India.[117] His artistic depictions are more numerous than those of any other god; prior to 430 BC, he is portrayed as a bearded and clothed adult, often adorned with an animal skin, while later representations depict him as a beardless, effeminate youth.[114] |

| Hephaestus Ἥφαιστος |

|

God of fire and metalworking.[118] He is the son of Hera, either on her own or by Zeus.[119] He is non-Greek in origin,[120] and his cult was likely imported from Asia Minor.[121] He was worshipped on the island of Lemnos, and more famously at Athens, where he was linked with Athena.[122] In Homeric epic he is the smith of the gods, who produces creations such as the shield of Achilles;[123] he has crippled feet, and is an outcast among the Olympians.[124] He is said to have been hurled from Olympus as an infant, either by Zeus, landing on Lemnos, or by Hera, landing in the sea.[125] His wife is Aglaea, one of the Charites, or the unfaithful Aphrodite.[119] In art, he is depicted wearing a pilos from the 5th century BC, and can be found holding an axe or hammer.[126] His Roman counterpart is Vulcan.[127] |

| Hera Ἥρα |

|

Wife of Zeus, and daughter of Cronus and Rhea.[128] She is associated with marriage in particular,[129] and is the queen of the gods.[130] She likely descends from a goddess who was worshipped in Mycenaean Greece.[131] She has some of the oldest sanctuaries, which often contain immense temples,[132] and her two most important locations of worship were the Heraion of Argos and Samos;[130] she was venerated in her role as the wife of Zeus, and as a city goddess.[131] By her husband she is the mother of Ares, Hebe, and Eileithyia,[133] and in myth she is a jealous wife who torments Zeus's mistresses and other children.[134] In artistic depictions of groups, she can sometimes be distinguished as a figure in bride's attire, accompanying Zeus, and in scenes of hieros gamos she is portrayed as a matronly figure; features of her depictions include clothing being pulled around her head like a veil, the patera, the sceptre, and pomegranate.[135] Her Roman counterpart is Juno.[136] |

| Hermes Ἑρμῆς |

|

Son of Zeus and the nymph Maia.[137] He is the messenger and herald of the gods,[138] the god of boundaries and their crossing,[139] and a trickster deity.[140] He is likely derived from a god which existed in Mycenaean Greece, and the most ancient location of his cult was the region of Arcadia, where his worship was especially prevalent;[141] his cult was spread through the Peloponnese, and existed in a particularly ancient in Athens.[142] He was closely linked with herms, stone statues which marked various boundaries, and was the patron of shepherds, especially young men whose job it was to protect crops from cattle.[143] He is said to have stolen the cattle of Apollo as a new-born, receiving the herd from the god by gifting him the lyre, which he had created from a tortoise's shell.[144] In art, his symbols include the caduceus, the petasos (or pilos), and his winged sandals; he is a bearded figure prior to the 4th century BC, after which beardless begin appearing.[145] His Roman counterpart is Mercury.[146] |

| Hestia Ἑστία |

|

Goddess of the hearth.[147] She is the daughter of Cronus and Rhea.[148] Her role in mythology is minimal,[149] and she is never fully anthropomorphic.[35] In cultic activity, she is always the deity who receives the first offering or prayer, and she was venerated in each city's communal hearth, or prytaneion.[150] She is a virgin goddess, who forever retains her chastity, and rejects the advances of male deities such as Apollo and Poseidon.[151] Her Roman counterpart is Vesta.[152] |

| Poseidon Ποσειδῶν |

|

God of the sea, earthquakes, and horses.[153] He is the son of Cronus and Rhea, and the brother of Zeus and Hades.[154] He was an important deity in Mycenaean Greece, and through the archaic period his position receded.[155] He had sanctuaries in many coastal locations, though he was also worshipped in inland areas, where he was associated with bodies of water such as pools and streams.[156] His epithets include Hippios (relating to horses), "Earth-Shaker", and "Embracer of Earth".[157] In the Iliad, he and his brothers split the cosmos between themselves, with Poseidon receiving the sea.[158] His wife is Amphitrite, with whom he lives below the ocean, though he has affairs with numerous women, producing sometimes dangerous or monstrous children.[159] From the 7th century BC, Corinthian votive tablets show him with his trident in hand, wearing a diadem and chiton; it can be difficult to tell apart him apart from Zeus, and only from the Hellenistic period is he found in a chariot pulled by hippocampi.[160] His Roman counterpart is Neptune.[161] |

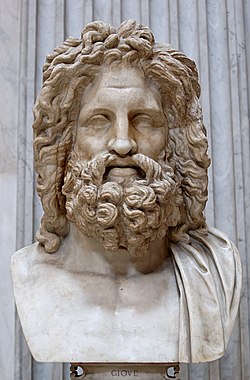

| Zeus Ζεύς |

|

Chief god of the Greek pantheon.[162] He is the king of the gods,[163] and the most powerful deity.[164] He is the son of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, and the husband of Hera.[165] He is the only Greek god who is unquestionably Indo-European in origin,[166] and he is attested already in Mycenaean Greece.[167] His numerous functions and domains are more varied than those of any other god, and over 1000 of his epithets survive.[168] According to Hesiod's Theogony, he attains his power by overthrowing his father and the other Titans in a ten-year war known as the Titanomachy.[169] Through his innumerable sexual exploits with mortal women, he was the father of various heroes and progenitors of well-known family lines.[170] Among his symbols are the thunderbolt, the sceptre, and the eagle.[171] In art from the 6th century BC onwards, he was often shown sitting on a throne, or as an upright figure wielding a lightning bolt; Zeus's lusting after women is also frequently found on vase paintings from the 5th century BC.[172] His Roman counterpart is Jupiter, also referred to as Jove.[173] |

Chthonic deities

| Name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hades Ἅιδης |

|

Ruler of the underworld and the dead.[174] He is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the consort of Persephone.[175] In the Iliad, Hades and his brothers, Poseidon and Zeus, split the world between themselves, with Hades receiving the underworld.[176] He was referred to under names such as Plouton and "chthonian Zeus", and his epithets included Clymenus ('Renowned') and Eubouleus ('Good Counsellor').[177] In his best-known myth, he kidnaps Persephone, after receiving Zeus's assent, and takes her into the underworld; while there, she consumes some of his food, forcing her to henceforth spend part of each year in the underworld.[178] He had virtually no role in cult, and was worshipped instead as Plouton, throughout Greece.[179] In artistic depictions he often holds a sceptre or key, with his appearance being similar to that of Zeus.[180] His name can also be used to denote to the underworld itself.[181] |

| Persephone Περσεφόνη |

|

Daughter of Zeus and Demeter.[182] She is the wife of Hades, and queen of the underworld.[183] In her central myth, first narrated in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, she is seized by Hades while frolicking in a meadow, and carried her into the underworld;[184] Zeus asks for her return, but Persephone, having consumed pomengranate seeds during her stay, is forced to from then on spend a part of each year there.[185] She is frequently found alongside her mother in cult, and the two are honoured in the Thesmophoria festival,[186] as well as the Eleusinian Mysteries;[187] she can also be found closely linked in cult with Hades.[188] She also appears in myth as the queen of the underworld, a realm over which she wields significant power, with her being described as helping certain mortals who visit.[189] |

| Plouton Πλούτων |

|

A name for the ruler of the underworld, who is also known as Hades.[190] Plouton is attested from around 500 BC,[191] before which he was a distinct deity from Hades;[179] the name is a euphemistic title, which alludes to the riches that exist beneath the earth.[190] Plouton appears in cult linked with Persephone and Demeter, and his worship is attested almost exclusively in Attica prior to the Hellenistic period, in relation to Eleusinian cult in particular.[192] In art, he is depicted with a beard (which is sometimes white), and carrying a cornucopia or sceptre.[193] |

Lesser deities

| Name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Eileithyia Εἰλείθυια |

|

Goddess associated with birth.[35] In the Theogony, she is the daughter of Zeus and Hera.[194] She is attested in the Bronze Age,[195] and was worshipped at a cave in Amnisos on Crete as early as the Middle Minoan period.[196] She was venerated mostly by women,[197] and in the archaic period her worship was found most prominently on Crete, in the Peloponnese, and in the Cyclades;[198] she is also worshipped in a number of locations as an aspect of Artemis.[199] |

| Enyalius Ἐνυάλιος |

A war god.[200] He is associated in particular with close-quarters fighting, though the degree to which he is a separate deity from Ares has been debated since antiquity.[201] He is mentioned as early as the Mycenaean period,[202] and his worship is most clearly attested in the Peloponnese; he possessed a significant cult at Sparta, where there sat a statue of him bound in chains.[203] In literature, he is little more than an epithet or byname for Ares.[204] | |

| Hecate Ἑκάτη |

|

A goddess associated with ghosts and magic.[205] In the Theogony, she is the daughter of Perses and Asteria.[206] She was likely originally from Caria in Asia Minor, and her worship seems to have been taken up by the Greeks during the archaic period.[207] She is attested in Athens in the sixth century BC, and statues of her stood guard throughout the city by the Classical period.[208] She is absent from Homeric epic, and Hesiod celebrates her in a section of his Theogony, treating her as a mighty goddess who helps various members of society.[209] She was said to have been accompanied by the ghosts of maidens and women who died childless, and was linked with dogs and their sacrifice.[210] Beginning in the 5th century BC, she was assimilated with Artemis.[197] In art, she is depicted with either one or three faces (and sometimes three bodies), and is frequently found wearing a polos and carrying torches.[211] |

| Pan Πάν |

|

God of shepherds and goatherds.[212] He comes from the region of Arcadia, and was conceived of as partly human and partly goat.[213] During the 5th century BC, his worship spread to Athens from Arcadia, before being dispersed across the Greek world;[214] he was venerated in caves, sometimes in conjunction with Hermes and the nymphs.[213] There were numerous conflicting versions of his parentage,[215] and in myth he is a figure who roams the mountains and plays the syrinx;[216] he is a lecherous figure who lusts after both nymphs and young men,[217] though he is typically met with little success in his lustful pursuits.[218] In art, he is portrayed as an ithyphallic figure.[219] |

| Prometheus Προμηθεύς |

|

Son of the Titan Iapetus.[220] He was credited with the creation of mankind, producing the first human from a lump of clay.[221] He was said to have brought fire to humanity, having covertly stolen it from Olympus; this action earned him the punishment of Zeus, who had him bound to a rock face in the Caucasus Mountains, where an eagle would tear apart his liver each day, before it regenerated over the following night.[222] He is later set free from his punishment by Heracles.[223] The image of his punishment is found in art as early as the 7th century BC, and he is typically found as a bearded figure with an unclothed body and arms bound, while the eagle hovers overhead.[224] |

| Leto Λητώ |

|

Mother of Apollo and Artemis by Zeus.[225] She is the daughter of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe.[226] When pregnant with her children, she travels to find somewhere give birth, but is rebuffed in each location (in some accounts due to the efforts of a jealous Hera), before arriving at Delos, where she eventually delivers both children (though in an early version Artemis is born instead on Ortygia).[227] In cult, she was frequently linked with her children,[228] though in Asia Minor she was more important as an individual, and from the 6th century BC she was worshipped at the Letoon in Lycia.[229] |

| Leucothea Λευκοθέα |

|

A sea goddess.[230] In myth, she was originally a mortal women named Ino, who fled from her frenzied husband with her young son, Melicertes, in her arms; she jumped into the sea, taking her son with her, and the two were deified, becoming Leucothea and Palaemon, respectively.[231] Leucothea was venerated across the Mediterranean world,[232] and was linked with initiation rites, a connection which is likely responsible for her identification with Ino.[233] |

| Thetis Θέτις |

|

The mother of Achilles.[234] She is one of the Nereids, the daughters of Nereus and Doris.[235] She is courted by Poseidon and Zeus until they hear of a prophecy that any son she bears will overthrow his father, prompting Zeus to wed Thetis to the hero Peleus.[236] Prior to their marriage, her future husband pursues her, with her transforming into different shapes as she flees.[237] After the birth of Achilles, she burns her son in an attempt to make him immortal, an action which led to the end of her marriage.[238] Her cult existed in Thessaly and Sparta,[232] and she was a popular subject in vase paintings, particularly in the 6th and 5th centuries BC.[239] |

Nature deities

| Name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Achelous Ἀχελώϊος |

|

One of the river gods, sons of Oceanus and Tethys.[240] He was the god of the Achelous River,[241] the largest river in Greece.[242] The oracle of Zeus at Dodona helped to spread his worship,[243] and he was often venerated alongside the nymphs,[244] though his cult began to recede in the 4th century BC.[243] In myth, he fights the hero Heracles for the hand of Deianeira, assuming multiple forms in the battle, including that of a bull; he is beaten when Heracles snaps one of his horns from his head.[245] |

| Anemoi Άνεμοι |

|

Personifications of the winds.[246] They are typically four in number – Zephyrus (West Wind), Boreas (North Wind), Notus (South Wind), and Eurus (East Wind)[247] – though Hesiod, who describes them as children of Eos and Astraeus, omits Eurus.[248] There survives a reference to a "Priestess of the Winds" from the Mycenaean period, and major deities, especially Zeus, were connected with winds.[249] In myth, Boreas was said to have kidnapped the Athenian princess Orithyia.[250] |

| Gaia Γαῖα |

|

Personification and goddess of the earth.[251] In Hesiod's Theogony, she is one of the earliest beings in existence, and the progenitor of an extensive genealogy,[252] producing figures such as Uranus and Pontus on her own, and the Titans, Cyclopes, and Hecatoncheires by Uranus.[253] She has the ability of prophecy, and was believed to have preceded Apollo at the oracle of Delphi.[254] In cult, she is more commonly referred to as Ge, and is often venerated alongside Zeus;[203] her worship existed primarily outside of the polis,[255] though Gē Kourotrophos was venerated in Athens.[256] |

| Helios Ἥλιος |

|

The sun and its god.[257] He is the son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia.[258] It was believed that he travelled through the sky each day in a horse-pulled chariot, making his way from east to west; each night he drifted back to the east in a bowl, through Oceanus (the river which wrapped around the earth).[259] Though the sun was universally viewed as divine in Classical Greece, it received relatively little worship;[260] the most significant location of Helios's cult was the island of Rhodes, where he was the subject of the Colossus of Rhodes.[261] He was commonly called upon in oaths, as it was believed he could witness everything across the earth.[262] He was assimilated with Apollo by the 5th century BC, though their equation was not established until later on.[263] |

| River gods ποταμοί |

|

The 3000 male offspring of Oceanus and Tethys, and brothers of the Oceanids.[264] River gods were often locally venerated in Greek cities, and they were seen as representations of a city's identity.[265] Their worship was developed by the time of Homer;[266] river gods were given a sanctuary in their city, and were given sacrifices of youths' hair.[39] The only river god worshipped throughout Greece was Achelous.[244] Their iconography includes the melding of the human form with bull-like features.[267] Other river gods include Eridanos, Alpheus, and Scamander.[268] |

Other deities in cult

| Name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Asclepius Ἀσκληπιός |

|

God of healing and medicine.[269] In mythology, he is described as a mortal hero,[270] with the usual tradition calling him the son of Apollo and Coronis;[271] while pregnant, Coronis weds the mortal Ischys, which leads Apollo to kill her, and he rescues the infant in the process.[272] Asclepius grows up to become a skilled healer, capable even of bringing the deceased back to life, an activity which leads Zeus to strike him down with lightning.[273] During the archaic era, his worship was likely centred in Tricca and Messenia, and towards the end of the period his cult seemingly spread further abroad.[274] His veneration at Epidauros started around 500 BC, and in the late 5th century BC he possessed two sanctuaries in Athens;[275] he was worshipped alongside family members, such as Hygieia, Machaon, and Podalirius.[276] Artistic depictions of Asclepius often portray him as a figure sitting on a throne, or an upright figure holding a staff laden with a snake.[277] |

| Cabeiri Κάβειροι |

|

A group of divinities venerated in mysteries.[278] Evidence of their worship is known primarily from the island of Lemnos and from Thebes,[279] though they are attested through the northern Aegean, in Thrace, and at Anthedon.[280] They originated from outside of Greece, though there is evidence of their worship in Thebes as early as the 7th century BC.[281] The gods of the Samothracian mysteries are called Cabeiri by some sources, though in epigraphic evidence from the island there is mention only of Megaloi Theoi ('Great Gods') or Theoi ('Gods').[282] The Cabeiri are commonly associated with other groups of divinities – such as the Kouretes, Corybantes, and Idaean Dactyls[283] – and their number varies according to the source.[284] Some authors call them the offspring of Hephaestus.[285] |

| Charites Χάριτες |

|

Goddesses who embody beauty, charm, and grace.[286] In the Theogony there are three Charites – Aglaea, Euphrosyne, and Thalia – who are the offspring of Zeus and Eurynome.[287] They were associated with Aphrodite, and were said to be her attendants.[288] The most famous location of their worship was Orchomenus,[289] where they were venerated in the form of three stones;[290] they were also worshipped in Athens and on the island of Paros.[195] In the Iliad, the Charis Pasithea is the wife of Hypnos, while in the Theogony Aglaea is married to Hephaestus.[291] |

| The Dioscuri Διόσκουροι |

|

A pair of divine twins named Castor and Polydeuces.[292] The Iliad places Helen of Troy as their sister and Tyndareus as their father, while in later sources Polydeuces is the son of Zeus.[293] They are generally considered Indo-European in origin,[294] and were venerated across Greece; Sparta was regarded as the primary location of their worship, though their cult was also very prominent in Attica.[293] In myth, they are often described as being involved in disputes with other pairs of mythical figures, including battling Lynceus and Idas after stealing their wives;[295] they were also said to have retrieved a kidnapped Helen from Attica.[296] Artistic representations depict them with symbols such as horses, piloi, and stars.[297] |

| Heracles Ἡρακλῆς |

|

The mightiest of the Greek heroes.[298] He is the son of Zeus and Alcmene,[299] and was considered both a hero and a god.[300] He was worshipped throughout the Greek world (though he received little veneration in Crete), and his cult resembled those of the gods.[301] His cult on the island of Thasos was among his oldest, he was worshipped in numerous locations in Attica,[302] and in Thebes his cult existed as early as the time of Homer.[303] He was said to have completed twelve labours on the command of Eurystheus,[304] though the canonical set of labours was established only by the early 5th century BC; most of these tasks involve him fighting monstrous beasts or humanoid creatures.[305] In art, scenes from his labours can be found from the 8th century BC,[306] and his attributes include his cape (made from the Nemean lion's fur), a club, and a bow.[307] |

| Muses Μούσαι |

|

Goddesses who were responsible for inspiring poets and other creative and intellectual figures.[308] In the Theogony, they are the nine daughters of Zeus and the Titan Mnemosyne.[309] Their earliest site of worship was on Mount Olympus,[310] and they possessed a sanctuary at the foot of Mount Helicon.[311] There were different sets of Muses said to come from different locations,[312] and particular areas of creative activity were believed to have been governed by individual Muses.[313] As a group, they are commonly associated with Apollo.[314] |

Foreign deities worshipped in Greece

| Name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Adonis Άδωνις |

|

A figure of Levantine origin.[315] He is born of the incestuous union between a Phoenician king and his daughter, Myrrha.[316] Though this genealogy places him as a mortal, in cult he was considered a god.[317] He is known to have been worshipped on Lesbos by the beginning of the 6th century BC,[318] and in Athens by the 5th century BC;[317] he was venerated primarily by women, who were the participants in the Adonia festival.[319] In myth, he is a young man of great beauty, who is loved by Aphrodite; because Persephone is also enchanted by his beauty, Zeus decrees he spend parts of the year with each goddess.[320] |

| Ammon Ἄμμων |

|

The principal deity of the Egyptian pantheon.[321] Due to his position in the pantheon, he was equated by the Greeks with Zeus.[322] He was worshipped at the Siwa Oasis from at least the 6th century BC,[323] and his oracle began to be broadly known in that century.[324] Greek attention towards Ammon was due primarily to the Greek colony of Cyrene in Libya,[324] and by the 4th century BC he was venerated in Athens.[325] |

| Cybele Κυβέλη |

|

A mother goddess from Asia Minor.[326] She is the Anatolian form of the Great Mother, and in Greece she was typically referred to as Meter.[327] During the 6th century BC, her worship proliferated through the Greek world, and in the same century she was introduced in Athens.[328] Upon the spread of her cult, she was identified with the Greek goddess Rhea, the mother of the first generation of Olympians, as well as other goddesses such as Gaia and Demeter;[329] she may have also been equated with an indigenous mother goddess.[330] In artistic depictions, she is found seated on a throne, accompanied by lions and holding a tambourine.[330] Her cult was officially introduced in Rome around the end of the 3rd century AD.[326] |

| Isis Ἶσις |

|

An Egyptian goddess.[331] In Egyptian mythology, she was the wife of Osiris, and the mother of Horus.[332] She was known to the Greeks as early as the archaic period, and possessed a temple in Athens by the 4th century BC.[333] In the Graeco-Roman world, she was a goddess who presided over the family,[332] and was a healer and protective figure.[334] Herodotus equates her with Demeter.[335] |

| Men Μήν |

|

A deity from western Asia Minor.[336] He was a moon god, and his worship is most clearly documented in Lydia and Phrygia.[337] He is attested from the 4th century BC, with the earliest evidence in the Hellenistic period originating from Greece, particularly Attica.[338] In art, he is often found with crescent moons extending up from his shoulders, wearing a Phrygian cap and sleeved clothes, and holding a sceptre or rod.[339] |

| Sabazios Σαβάζιος |

|

A god from Phrygia in Asia Minor.[340] His earliest literary attestion is from the 5th century BC,[341] and his worship in Attica is mentioned in the 4th century BC.[342] He was identified with Dionysus, and an Orphic myth of Dionysus's birth to Zeus and his daughter, Persephone, was linked with the mysteries of Sabazios.[343] In artistic depictions, he is portrayed as a bearded figure in Phrygian garb, or as having the iconography of Zeus-Jupiter; there also exist votive hands dedicated to him, which hold objects such as snakes or pine cones.[344] |

| Serapis Σέραπις |

|

A god derived from the syncretic Egyptian figure Osiris-Apis.[345] This Egyptian antecedent had a cult in Memphis, where he was a sacred bull figure.[346] This cult was adapted by the Greeks into that of Serapis;[347] the first three Ptolemies had a Serapeum constructed in Alexandria,[348] and Ptolemy I Soter was said to have brought to the city a statue of Pluto, which was given the name of Serapis.[349] The god was identified with Greeks deities such as Dionysus, Pluto, and Zeus,[350] and in art he was depicted wearing a calathus atop his head.[351] His worship propagated in the Mediterranean, and he possessed temples in Athens and Corinth.[352] |

Early deities

This section is structured after the chapter "1. The Early Gods" in Timothy Gantz's Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources.[353]

Primal elements

-

Aether (right)

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Aether | Personification of the brightness present in the upper sky.[354] In the Theogony, he is the offspring of Nyx and Erebus, and the brother of Hemera.[355] He appears a number of other early cosmogonies,[356] while in an Orphic theogony, he is produced by Chronos, alongside Chaos and Erebus.[357] |

| Chaos | The first being to exist in Hesiod's Theogony.[358] The word means 'yawning' or 'gap', though the location of Chaos, or what it sits between, is not specified.[359] After Chaos there came Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros, and from Chaos itself was born Erebus and Nyx.[360] |

| Erebus | Personification of darkness.[361] In the Theogony, he is the offspring of Chaos, and the brother of Nyx, with whom he produces Aether and Hemera.[362] In an Orphic theogony, he is produced by Chronos.[363] The word is often also used to refer to the underworld.[364] |

| Eros | God of love.[365] He is typically considered the son of Aphrodite,[366] though in the Theogony he is among the earliest beings to exist.[367] In other cosmogonies, he is similarly conceived of as a primordial figure, a depiction which can also be found in Orphic literature.[368] He is absent from Homeric epic, and lyric poets of the archaic era present him as a representation of the subjective experience of love.[369] He features as part of Aphrodite's retinue alongside figures such as Himeros and Pothos.[370] In Thespiai, he was venerated in the form of a stone,[371] and in cult he typically appears alongside Aphrodite.[372] The Romans referred to him as Cupid or Amor.[373] |

| Gaia | See § Nature deities. |

| Hemera | The personification and goddess of the day.[374] In the Theogony, she is the offspring of Nyx and Erebus, and the sister of Aether.[375] Hemera and Eos are frequently identified in later works.[376] |

| Nyx | The goddess and personification of the night.[377] In the Theogony, she the is offspring of Chaos, and the sister of Erebus, by whom she becomes the mother of Aether and Hemera.[378] Without the help of a father, she gives rise to a dismal brood of negative personifications.[379] She is said to live at the extremes of the earth or in the underworld, and to drive a horse-pulled chariot.[380] In the Iliad, even Zeus fears to upset her,[381] and she figures prominently in early cosmogonies.[356] In the oldest known Orphic theogonies, Nyx appears to have been the first deity,[382] while in the Orphic Rhapsodies she is a ruler who supplants Phanes.[383] |

| Tartarus | A region which sat far below the underworld,[384] and its personification.[385] In the Theogony, he is one of the first beings to come into existence, appearing after Gaia and prior to Eros.[386] By Gaia, he becomes the father of the monstrous offspring Typhon and (in later sources) Echidna.[387] |

Descendants of Gaia and Uranus

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Aphrodite | See § Twelve Olympians. |

| Erinyes | Figures that punish those who commit serious offences, particularly against family members.[388] Their names are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone.[389] In the Theogony, they are produced from blood spilling onto the earth when Uranus is castrated by his son, Cronus;[390] elsewhere they are offspring of Nyx.[391] They are said to be inhabitants of the underworld, and to be capable of cursing mortals, or driving them mad.[392] Erinys (the singular from of "Erinyes") was assimilated to Demeter in Arcadia, and was considered the mother of Arion by Poseidon.[393] The Roman counterparts of the Erinyes are the Furies.[394] |

| Meliae | Considered by most scholars to be nymphs of ash trees.[395] According to the Hesiod, they are born from drops of blood which are spilt when Uranus's genitals are severed.[396] |

| Ourea | The mountains.[397] In the Theogony, they are produced by Gaia without the aid of a father.[398] |

| Pontus | Personification of the sea.[399] In the Theogony, he is the offspring of the Gaia, who produces him without a father.[400] By Gaia, he fathers Eurybia, Nereus, Thaumas, Phorcys, and Ceto.[401] |

| Uranus | Personification of the sky.[402] He is the offspring of Gaia, who produces him without the help of a partner.[403] By Gaia, he fathers the Titans, the Cyclopes, and the Hecatoncheires;[404] he imprisons his offspring within the earth, leading his Titan son Cronus to castrate him.[405] He hurls the severed genitals into the ocean, and the blood spilt onto the earth in time produces the Erinyes, Giants, and Meliae.[406] |

Descendants of Gaia and Pontus

-

A Nereid

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Anemoi | See § Nature deities. |

| Astraeus | Son of Crius and Eurybia.[407] He is the husband of Eos, by whom he becomes the father of the winds – Boreas, Zephyrus, and Notus – as well as the stars, including Eosphorus.[408] |

| Ceto | Daughter of Gaia and Pontus.[401] She is the wife of the sea god Phorcys, by whom she produces a brood of monstrous creatures, including the Gorgons, the Graeae, and Echidna.[409] |

| Eosphorus | The morning star.[410] He is one of the children of Eos and Astraeus,[411] and his offspring across different sources include Stilbe, Philonis, and Leuconoe.[412] His Roman counterpart is Lucifer.[413] |

| Eurybia | Daughter of Gaia and Pontus.[414] She is the wife of the Titan Crius, by whom she becomes the mother of Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.[415] |

| Hecate | See § Lesser deities. |

| Iris | Messenger of the gods and the personification of the rainbow.[416] She is considered the daughter of Thaumas and Electra, and at times the wife of Zephyrus.[417] In the Iliad, as divine messenger she acts mostly upon the orders of Zeus, though she also acts independently in some instances;[418] in later works, she instead serves Hera.[419] She sometimes transforms into another figure during a task, and her epithets in the Iliad emphasise her swiftness.[416] In artistic depictions, she is commonly portrayed as a winged figure who carries a staff, and is often found accompanying more important deities.[420] |

| Nereus | A sea god, and son of Gaia and Pontus.[421] He is the husband of Doris, by whom he becomes the father of the fifty Nereids, who live with him beneath the sea.[422] He is one of the deities referred to as an "Old Man of the Sea", and is described as having prophetic abilities and being capable of shapeshifting.[423] He was said to battled the hero Heracles, changing himself into numerous forms during the struggle; this myth is a common subject in vase painting, with him having the tail of a fish in the earliest depictions, and having legs in later works.[424] |

| Nereids | Sea nymphs, who are the fifty daughters of Nereus and Doris.[425] Different enumerations of Nereids are given by different authors,[426] and only a handful – such as Thetis, Galateia, Amphitrite, and Psamathe – have any meaningful role in myth.[422] They live with their father at the bottom of the sea, and were said to partake in song and dance.[427] In art, they are often found riding marine animals, accompanying a sea deity such as Poseidon; from the 4th century BC, they can be found partially or fully naked, and are occasionally found with fishtails.[427] |

| Pallas | A Titan.[428] In the Theogony he is the husband of Styx, and the father of Zelus, Nike, Kratos, and Bia.[429] Elsewhere Eos is given as his daughter.[430] |

| Perses | Son of Crius and Eurybia.[431] With Asteria, he produces the goddess Hecate.[432] Hesiod states that he is exceptionally wise.[433] |

| Phorcys | An early sea god.[434] He is most often considered the offspring of Gaia and Pontus.[435] His wife is Ceto, with whom he produces a series of monsters, such as the Gorgons, the Graeae, and Echidna.[436] He is referred to as an "Old Man of the Sea" in the Odyssey, and called the father of Thoosa;[437] figures elsewhere given as his offspring include the Sirens, the Hesperides, and Scylla.[438] |

| Thaumas | He is the offspring of Gaia and Pontus.[439] His wife is Electra, by whom he becomes the father of the goddess Iris and the Harpies.[440] |

The Titans and their descendants

-

Eos (winged)

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Asteria | Daughter of Coeus and Phoebe.[441] In the Theogony, she marries Perses, and the two give rise to Hecate.[442] It was said that when Zeus chased lustfully she ended up falling into sea, and was transformed into a quail; in the place she landed would rise the island, sometimes called Asteria, on which her sister Leto would later give birth.[443] |

| Atlas | The offspring of the Titan Iapetus and an Oceanid, either Clymene or Asia.[444] He was said to stand at the edge of the earth (in the far west or far north), and hold up the sky;[445] the earliest sources for the punishment give no explicit reason as to why he was given this burden,[446] though later authors believed it was due to his role in the Titanomachy.[433] A story from the Metamorphoses tells that Perseus encounters Atlas and caused him to become a mountain, using the severed head of Medusa; it was also said that he was approached by Heracles, who tricked Atlas and stole the golden apples from the nearby garden of the Hesperides.[447] |

| Coeus | One of the Titans, children of Uranus and Gaia.[448] He marries Phoebe, with whom he produces Leto, the mother of Artemis and Apollo, and Asteria.[449] |

| Crius | One of the Titans, offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[450] His wife is Eurybia, by whom he becomes the father of Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.[451] |

| Cronus | The youngest of the Titans, the offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[452] He was chief among the Titans, and was the ruler prior to Zeus.[453] He is said to have castrated his father with a sickle, overthrowing him, and becoming a tyrant; he swallows each child he has by his sister Rhea, until she hands him a stone to swallow in place of their final child, Zeus.[454] Once grown, Zeus forces Cronus to disgorge his other children, who side with Zeus in a battle against the Titans, with Cronus and his siblings being defeated and banished to Tartarus.[455] In Hesiod's Works and Days, Cronus's reign is contrastingly described as an idyllic age in which a golden race of humans lived.[456] He was honoured in the Kronia festival, which was associated with the harvest, and he possessed a temple in Olympia.[457] His Roman counterpart is Saturn.[458] |

| Dione | A consort of Zeus in some sources.[268] In the Bibliotheca of Apollodorus, she is one of the Titans.[459] Homer places her as the mother of Aphrodite (presumably by Zeus), and in the Theogony she is listed as one of the Oceanids.[460] She was possibly the wife of Zeus prior to the Mycenaean era, by which point Hera existed in this role.[461] Dione was venerated as his consort at the oracle of Dodona, and the name "Dione" is a feminine version of "Zeus".[462] |

| Eos | Goddess of the dawn.[463] She is the daughter of Hyperion and Theia.[464] WIth Astraeus, she produces the winds – Boreas, Zephyrus, and Notus – as well as the stars, including Eosphorus.[465] She is said to drive a chariot up from the horizon at the beginning of each day.[466] In myth, she steals away a number of young mortal men with amarous intent, as in the stories of Tithonus, Orion, and Cleitus; she lived with Tithonus, who Zeus granted immortality (but not eternal youth), and the couple produced two children – Emathion and Memnon – before Tithonus slowly began to deteriorate.[467] She is found in art from the 6th century BC, and is typically portrayed as a winged figure.[468] |

| Epimetheus | Son of Iapetus and Clymene or Asia.[469] His brother, Prometheus, cautions him to refuse all gifts from Zeus, but when the gods create Pandora, the first woman, and Zeus has her sent to Epimetheus, Prometheus's foolhardy brother accepts her; the two are married, and as a result she is brought among mortals, allowing her to unleash upon them the evils from her jar.[470] |

| Helios | See § Nature deities. |

| Hyperion | One of the Titans, the offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[471] His consort is Theia, by whom he becomes the father of Helios, Selene, and Eos.[472] He was frequently equated with Helios, and Homer uses "Hyperion" as an epithet of the god.[473] |

| Iapetus | One of the Titan offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[474] In the Iliad, he is mentioned as a Titan who Zeus banishes to Tartarus.[475] In Hesiod's Theogony, he is the father Prometheus, Epimetheus, Atlas, and Menoetius, and the husband of Clymene, though other sources give his consort as Asia.[476] |

| Leto | See § Lesser deities. |

| Menoetius | Son of Iapetus and either Clyemene or Asia.[477] Due to his hubris, he is struck with lightning by Zeus, and hurled down to Tartarus.[478] |

| Metis | One of the Oceanids, offspring of Oceanus and Tethys.[479] In the Theogony, she is the first goddess Zeus marries;[480] when he hears that she is destined to bear a child who will overthrow him, he swallows her.[481] Metis, pregnant with Athena, births her daughter inside Zeus, with her emerging from his head; Metis exists within him permanently, a position from which she provides him counsel.[482] In Apollodorus's account, she aids Zeus against his father, Cronus, by delivering the latter an emetic, which frees Zeus's siblings from his father's stomach.[483] |

| Mnemosyne | Personification of memory.[484] She is the one of the Titan daughters of Uranus and Gaia.[485] In the Theogony, she lies with Zeus for nine consecutive nights, resulting in the birth of the nine Muses.[486] She had some existence in cult, and is known to have been venerated in conjunction with the Muses in particular.[487] |

| Oceanids | Ocean nymphs, the 3000 female offspring of Oceanus and Tethys.[488] The forty-one oldest Oceanids are enumerated in the Theogony, and other lists are given in later works.[489] They are said to be protectors of the young,[490] and a group of them features in the retinue of Artemis, while others are mentioned as companions of Persephone before her abduction.[491] Individual Oceanids include Styx, Doris, Metis, and Peitho.[492] |

| Oceanus | God of the river believed to encompass the earth and give rise to all other water bodies.[493] He is one of the Titans, the offspring of Gaia and Uranus.[494] His wife is Tethys, by whom he is the father of the 3000 Oceanids and the 3000 river gods.[495] Homer appears to call him the forefather of the gods.[496] A number of peoples and monsters were said to existed next to Oceanus, at the far extent of the world.[497] Artistic depictions portray him as being part human and part marine creature.[498] |

| Phoebe | A female Titan, one of the offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[499] Her husband is her brother Coeus, by whom she becomes the mother of Leto and Asteria,[500] and thereby the grandparent of Apollo and Artemis.[501] In some accounts, she is credited as the founder of the Delphic oracle, who passes it on to Apollo.[499] |

| Prometheus | See § Lesser deities. |

| Rhea | One of the female Titans, daughters of Uranus and Gaia.[502] She was the wife of Cronus, and the mother of Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus.[503] Her husband swallows each child upon their birth, until Rhea hides away their final child, Zeus, instead delivering Cronus a stone to consume; once grown, Zeus wages war against Cronus, during which Rhea has Oceanus and Tethys look after Hera.[504] As early as the 5th century BC, Rhea was identified with Cybele.[505] |

| River gods | See § Nature deities. |

| Selene | Goddess and personification of the moon.[506] In the Theogony, she is the offspring of Hyperion and Theia.[507] She is said to have fallen for the beautiful Endymion, who slept permanently, and the two produced fifty daughters.[508] She also has an affair with Pan, and births Pandia and Ersa to Zeus.[509] She is found in art from the early 5th century BC, and is depicted flying her horse-pulled (or oxen-pulled) chariot through the sky, though she can also be found on horseback.[510] |

| Styx | The goddess of the river Styx, the primary river of the underworld.[511] She is the oldest of the Oceanids, the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys,[512] and is the wife of Pallas, with whom she produces Zelus, Nike, Kratos, and Bia.[513] She aids Zeus and the younger gods in the Titanomachy, for which Zeus makes swearing upon her waters the highest oath of the gods.[514] She was said to reside in the underworld,[515] and the river said to encircle that realm.[516] |

| Tethys | One of the Titans, offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[517] She is the wife of her brother Oceanus, by whom she becomes the mother of the 3000 river gods and 3000 Oceanids.[500] In the Iliad, she and her husband are mentioned as progenitors of the gods.[518] During Zeus's battle against the Titans, Hera is sent to stay in the abode of Oceanus and Tethys at the far extremes of the earth; the couple, who had become alienated, were brought together again by Hera.[519] |

| Theia | One of the female Titans, offspring of Uranus and Gaia.[520] She is the wife of Hyperion, by whom she becomes the mother of Helios, Selene, and Eos.[521] |

| Themis | One of the Titans, a daughter of Uranus and Gaia.[522] Hesiod names her as the second goddess married by Zeus, with their union producing the three Horae and three Moirai.[523] She is the goddess who presides over "sacred ancient law",[524] and is the figure who provides counsel to Zeus.[525] Aeschylus names her as the mother of Prometheus, and equates her with Gaia.[526] She possessed the power of prophecy, and delivers oracles (including that which stops Zeus from wedding Thetis); she is also said to been an owner of the Delphic oracle prior to Apollo.[527] She was worshipped in a number of locations, including at Rhamnous, where she was venerated in conjunction with Nemesis.[528] |

Groups of divinities and nature spirits

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Cabeiri | See § Other deities in cult. |

| Charites | See § Other deities in cult. |

| Dactyls | Figures described as companions of Rhea (or at times Cybele) whose name translates as 'fingers'.[529] In the Phoronis, they are three in number, and are companions of Adrasteia who originate from Ida.[285] Elsewhere they are more numerous, with other souces describing them as ten or 100 in number.[530] They are variously described as metal-workers or magicians,[531] and are at times equated with the Kouretes and considered protectors of the young Zeus.[532] |

| Horae | The Seasons,[533] daughters of Zeus and Themis.[534] They are three or four in number,[535] with Hesiod naming them as Eunomia, Dike, and Eirene;[536] in Athens, they instead called Thallo, Auxo, and Carpo.[537] They are connected with plant life, and with order,[538] and Homer states that they stand guard outside the entrance to Olympus.[539] There is attestion of a cult belonging to the Horae, including a sanctuary in Attica; in art, it is often impossible to tell them apart from the nymphs and Charites.[540] |

| Korybantes | Figures who accompany Cybele.[541] They were commonly equated with the Kouretes, and are similarly described as dancers who clang their spears upon their shields.[542] They are ascribed numerous parentages in different sources, with Apollo or Rhea frequently being named as one of their parents.[543] |

| Kouretes | Figures who protect the young Zeus, by producing a din with their spears and shields, so that the child's crying cannot be heard by his father, Cronus.[544] When their number is specified, it is at times given as two or nine.[545] The location in which they protect Zeus is usually said to be Mount Dicte in Crete, though sometimes it is given as Mount Ida.[546] A fragment of Hesiod calls them offspring of the daughters of Dorus,[547] and they were often conflated with the Korybantes.[548] Their cult was spread across Crete, and existed in locations such as Olympia, Ephesus, and Messenia, with the island of Thera being an early location of worship.[549] |

| Maenads | Female figures in the retinue of Dionysus, who followed him in his travels.[550] Artistic depictions portray them as nude or scantily clad women, shown holding thyrsi or kantharoi, or musical instruments such as flutes or tambourines.[551] The nymphs who nursed the young Dionsyus were said to have become the first Maenads.[552] The term is also used to refer to the historical women who took inspiration from the mythical Maenads.[553] |

| Muses | See § Other deities in cult. |

| Nymphs | Female divinities connected with nature, and conceived of as human women.[554] There are a number of types of nymphs, some of which are connected to certain habitats – such as the dryads (tree nymphs), Oreads (mountain nymphs), or Meliae (ash tree nymphs) – while others are of a specific parentage, such as with the Nereids (daughters of Nereus) or Oceanids (daughters of Oceanus).[555] They are mortal, and are typically found in groups, with nymphs frequently being included as part of a nature-dwelling god's retinue.[556] Their cult is attested by the time of Homer, and their worship was connected with caves in particular, and with the veneration of the river gods.[557] The term was sometimes used more generally to refer to young women.[558] |

| Satyrs | Male figures who live in the wilderness.[559] They are first found around the start of the 6th century BC, and are among the figures in Dionysus's retinue.[560] They are depicted as part-human and part-animal, ithyphallic, and tailed;[561] while early representations show them with horse-like features, they gradually become closer to humans, before becoming more goat-like during the Hellenistic era.[562] They are generally shown as nude, bald, and snub-nosed, with their equine features extending to their ears and tail, as well (less often) their feet.[563] They are first mentioned in literature in a fragment of Hesiod, which calls them offspring of daughters of Dorus, as well as "worthless" and "good-for-nothing".[564] In myth, they are often found lusting after nymphs.[565] Their Roman counterparts are the fauns.[566] |

| Silenoi | Companions of Dionysus, who live in the wild.[567] They are first mentioned in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, where they are said to be sexual partners of the mountain nymphs.[568] In art, they seem to be identical in appearance to the satyrs;[560] they are perhaps the same figures as the satyrs, though they may have initially been separate.[569] |

| Telchines | Magical figures from the island of Rhodes.[570] They were believed to be the original inhabitants of a number of islands in the Aegean Sea, especially Rhodes.[571] They are said to be magicians and shapeshifters, and in art are portrayed as amphibious creatures who are part-fish or part-snake.[572] They were sometimes said to have invented metal-working, and different authors credit them with the creation of objects such as the Trident of Poseidon, or the sickle of Cronus.[573] |

| Thriae | Prophetesses who are be offspring of Zeus.[574] They are nymphs belonging to Mount Parnassus, and are three in number; they are said to among the first to practice divination, doing so through the use of pebbles.[575] |

Abstract personifications

| Name | Personified concept | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Achlys | Misery, sadness[576] | In the Shield of Heracles, she is one of the figures pictured on Heracles' shield. Her Latin counterpart, Caligo, is a said to be the parent of Chaos and Nox in the Fabulae.[577] |

| Adephagia | Satiety[578] | Demeter Adephagia was the subject of a temple in Sicily.[579] |

| Adikia | Injustice[580] | Her earliest attestation is a representation on the Chest of Cypselus, mentioned by Pausanias, showing her being pummeled by Dike.[581] The pair are also depicted on two Attic vases from the 6th century BC; Adikia is portrayed as an ugly figure in art, and is shown with spots in one depiction.[582] |

| Agon | Athletic contests[583] | There existed a statue of him at Olympia.[584] |

| Aidos | Shame or modesty[585] | She is mentioned in the Works and Days, and Sophocles states she is able to see all actions that are taken.[586] In Plato's story of Protagoras, Aidos approaches humankind alongisde Dike, who is sent by Zeus.[587] |

| Alala | The war cry[588] | According to Pindar, she is the daughter of Polemos.[589] |

| Alastor | The curse of generational guilt[590] | He features in tragedy, and is described as the figure who enacts vengeance for wicked actions, though for Aeschylus he is a daimon who is pernicious in nature, but unassociated with vengeance.[591] |

| Aletheia | Truth[592] | She was said to the offspring of Zeus, and to have nurtured Apollo during his childhood.[593] |

| Algea | Pains[403] | They are daughters of Eris.[594] |

| Alke | Valour[595] | In the Iliad, she is depicted on the aegis.[595] |

| Amechania | Impossibility[596] | One of the gods belonging to the people of Andros according to Herodotus.[597] |

| Amphilogiai | Verbal exchanges[598] | They are offspring of Eris.[599] |

| Anaideia | Shamelessnes[600] | |

| Ananke | Necessity or compulsion[601] | She is first attested as a cosmic goddess in the 5th century BC, appearing in the works of Parmenides, Simonides, and Empedocles.[602] In the Hieronyman Theogony, attributed to Orpheus, she produces Aether, Chaos, and Erebus by Chronos.[603] In the Hellenistic period, she is identified with Adrasteia.[604] In Plato's Republic, she is the mother of the Moirai.[605] |

| Androktasiai | Slaughter of men during war[606] | They are offspring of Eris in the Theogony.[607] |

| Angelia | Report[608] | According to Pindar, she is the daughter of Hermes.[609] |

| Anteros | Requited love[610] | He was said to punish those who do not reciprocate love.[610] He possessed an altar in Athens nearby to the Acropolis, and was depicted alongside Eros in a relief that existed in Elis.[611] |

| Apate | Deceit[612] | In Hesiod's Theogony, she is of the offspring of Nyx.[613] In an Orphic fragment, she and Zelus receive Aphrodite after her birth from the sea, and in the Dionysiaca she possesses a girdle that contains all forms of deceit.[614] |

| Apheleia | Simplicity, "the good old days"[615] | Eustathius calls her the nurse of Athena.[615] |

| Ara | The curse[616] | Aeschylus identifies her with Erinys.[616] |

| Astrape | The lightning bolt[617] | She was present on several lost works of art, including a painting by Apelles and a depiction of Semele's death; in representations, he is connected with Bronte.[618] |

| Ate | Delusion[619] | She is said to have deceived Zeus, and then been hurled down from Olympus by him as punishment; she landed on a hill in Phrygia, in the location in which Troy would later be founded.[620] In the Iliad she is the daughter of Zeus, while in the Theogony she is one of the offspring of Eris.[621] |

| Bia | Violence[622] | She is the offspring of Pallas and Styx, and alongside her siblings – Kratos, Nike, and Zelus – she is said to live on Mount Olympus, where she serves Zeus.[623] According to Aeschylus, she helps Hephaestus attach Prometheus to a rock after his deception of Zeus.[624] |

| Bronte | Thunder[625] | She appears in the proem of the Orphic Hymns, and is at times found alongside Sterope and Astrape.[626] She was represented in several works of Greek and Roman art, including a painting by Apelles.[627] |

| Caerus | The "opportune moment"[628] | He is attested from the 5th century BC, with him being called the son of Zeus, and he was worshipped at Olympia. In art, he is depicted as a winged figure with a tuffet of hair on the front of his head.[629] |

| Chronos | Time[630] | In the cosmogony of Pherecydes of Syros he is a primeval figure, and he is a significant figure in Orphic theogonies.[631] In the Hieronyman Theogony, attributed to Orpheus, he is a winged, serpentine figure with the heads of a lion and bull;[632] in the same work he produces Aether, Chaos, and Erebus with Ananke.[603] Later sources sometimes conflate him with the Titan Cronus.[633] |

| Corus | Surfeit[634] | He is the offspring of Hybris.[635] |

| Deimos | Fear[636] | Hesiod calls him the son of Ares and Aphrodite, and in the Iliad he is a companion of Ares alongside his brother, Phobos.[637] According to the Aspis, the two are his charioteers.[638] |

| Dike | Justice[639] | In the Theogony, she is one of the three Horae, offspring of Zeus and Themis.[640] She is intimately connected with Zeus, and is sometimes said to sit next to his throne, acting as his delegate and keeping a record of sinful actions for him.[641] She was depicted on the Chest of Cypselus as a beautiful figure, who strangles the ugly Adikia.[642] Hesychia is said to be her daughter, and Poena her assistant.[643] |

| Dysnomia | Lawlessness[644] | In the Theogony, she is one of the offspring of Eris.[645] |

| Eirene | Peace[646] | Hesiod lists her among the three Horae, offspring of Zeus and Themis.[647] There existed a cult to her in Athens from the 4th century BC, and she is depicted on vases from Attica; several of her cults are attested during the Hellenistic period.[648] |

| Eleos | Compassion[649] | There existed an altar honouring him in Athens.[649] |

| Eleutheria | Freedom[650] | She is said to be the daughter of Zeus, and is also called an attendant of Aletheia. She appears on a number of coins.[650] |

| Elpis | Hope[651] | In Hesiod's Works and Days, she is the only personification who stays inside in Pandora's jar when she opens, releasing the evils contained therein upon humanity.[652] |

| Eris | Strife[653] | In the Theogony she is among the gloomy offspring of Nyx, while in the Iliad she is Ares' sister.[654] In the Works and Days, there are two figures named Eris, one the daughter of Nyx and another less negative in nature.[655] She is said to have indirectly led to the start of the Trojan War by tossing a golden apple into the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, causing the Judgement of Paris.[656] |

| Ersa | Dew[657] | According to Alcman, she is the daughter of Zeus and Selene.[658] |

| Eucleia | Glory from a day of fighting[659] | There existed a sanctuary in Athens in honour of both her and Eunomia.[660] According to Plutarch, her parents were sometimes considered to be Heracles and Myrto, though she was also conflated with Artemis by some.[659] She is found alongside Eunomia on vases from the 5th century BC.[661] |

| Eulabeia | Caution[662] | In Euripides' Phoenician Women, Eteocles asks her to save Thebes.[662] |

| Eunomia | Good order[663] | In Hesiod's Theogony, she is one of the three Horae, daughters of Zeus and Themis.[664] She was considered a protector of peace, and during the 5th century BC her name was used in politics.[665] She is represented in 5th-century BC vase paintings alongside Eucleia, and she possessed a cult in Athens.[666] |

| Eupraxia | Success[667] | According to Aeschylus's Seven Against Thebes, she is the daughter of Peitharchia.[582] |

| Eusebeia | Piety[668] | She is the mother of Dike in Orphic literature, and is mentioned in the proem of the Orphic Hymns. A figure with this name is depicted on a number of Alexandrian coins.[668] |

| Gelos | Laughter[669] | Plutarch mentions a Spartan sanctuary in his honour, and Apuleius states that he was worshipped in the city of Hypata.[669] |

| Geras | Old age[670] | In the Theogony, he is among the offspring of Nyx, and in a late tale he helps Sisyphus escape the underworld.[671] He is said to have fought Heracles, and to live on Olympus.[672] |

| Hedone | Desire, joy, pleasure[673] | She appears as an allegorical personification in words of Greek philosophy. Apuleius names her parents as Cupid and Psyche.[674] |

| Heimarmene | Fate[675] | She is depicted on a 5th-century BC vase by the Heimarmene Painter.[676] |

| Himeros | Affectionate longing[677] | In the Theogony, he, alongisde Eros, accompanies Aphrodite after she is born from the sea, and he resides on Olympus.[678] In art, Himeros is identical in appearance to Eros.[679] |

| Homados | Tumult[680] | In Hesiod's Shield of Heracles, he is depicted on Heracles' shield.[681] |

| Homonoia | Concord, unanimity, oneness of mind[682] | She is known from the 4th century BC onwards, with there being early evidence of her cult in Olympia, Athens, and elsewhere.[683] According to Mnaseas, her parents are Zeus Soter and Praxidike.[682] She is represented on several Greek coins and a vase.[684] |

| Horkos | Curse resulting from swearing a false oath[685] | In the Theogony, Hesiod places her among the offspring of Eris, and in the Works and Days he writes that the Erinyes helped with his birth.[619] According to Sophocles, he is Zeus's son.[686] |

| Horme | Energetic activity[687] | Pausanias mentions an altar to her in the agora of Athens.[688] |

| Hybris | Lack of restrain, insolence[689] | In one version of Pan's parentage, she is his mother by Zeus.[216] |

| Hypnos | Sleep[690] | According to Hesiod, he is among the offspring of Nyx, and lives beside his brother Thanatos at the furthest reaches of the earth.[691] In the Iliad, he and Thanatos carry the deceased Sarpedon to Lycia, an episode that appears on vase paintings.[692] Elsewhere in the work, Hera requests he lull Zeus to sleep, and Hypnos protests that after a previous attempt to do so he had to escape Zeus's wrath; she persuades him by offering Pasithea in marriage.[693] In art, he is typically a young, winged figure, and alongside Thanatos he is depicted on the Chest of Cypselus.[694] |

| Hysminai | Combat[695] | In the Theogony, they are offspring of Eris, and Quintus Smyrnaeus names them among the personifications found on Achilles' shield.[696] |

| Ioke | Pursuit[697] | In the Iliad, she is among the personifications depicted on the aegis.[697] |

| Kakia | Vice[698] | In an allegory by the philosopher Prodicus, Heracles must choose either Arete (the personification of Goodness) or Kakia, the latter of whom tells the hero she is also called Eudaimonia. She is also found in works by Athenian orators.[699] |

| Keres | Inevitability of death[700] | Female figures who, according to Hesiod, are daughters of Nyx who wear blood-covered clothing. In the Iliad, they are said to cause disaster, and to steal human bodies and take them into the underworld, before consuming them.[701] In sources of the classical period, they can be conflated with similar figures such as the Moirai.[702] |

| Kratos | Power[703] | In the Theogony, he is among the offspring of Pallas and Styx, and is the brother of Bia.[704] Alongside his siblings, he accompanies Zeus, and in Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound he and Bia urge Hephaestus to fasten Prometheus to a rock.[705] |

| Kydoimos | Tumult of battle[706] | In the Iliad, he is found on the shield of Achilles.[707] |

| Lethe | Oblivion[708] | She is among the offspring of Eris, and was sometimes said to be the mother of Dionysus or the Charites.[709] Lethe, the underworld river, received its name from her.[710] |

| Limos | Hunger[711] | She one of the offspring of Eris.[711] |

| Litae | Prayers of contrition[712] | In the Iliad, they are daughters of Zeus and are said to answer prayers which display sufficient respect.[713] |

| Lyssa | Rage, frenzy, and madness[714] | She is first attested in 5th-century BC tragedy, appearing in Euripides as a daughter of Nyx and drives Heracles to insanity, causing him to murder his family.[715] He also describes her as a huntress who drives a chariot, and has snakes surrounding her face. In Aeschylus, she brings madness upon the Minyades, who dismember someone as a result.[716] |

| Machai | Wars[717] | In the Theogony, they are daughters of Eris.[695] |

| Maniae | Madness[718] | They were worshipped in Maniae, close to Megalopolis. Mania (the singular form of Maniae) is depicted on an Italian vase.[718] |

| Momus | Fault-finding[719] | In the Cypria, Zeus intends to eradicate humanity with flooding and lightning, until Momus suggests instead starting a devastating war, leading to the beginning of the Trojan War.[720] Hesiod includes him among the children of Nyx.[721] |

| Moros | Destiny[722] | In the Theogony, he is one of Nyx's offspring.[723] |

| Neikea | Quarrels[724] | According to Hesiod, Neikea is one of Nyx's children.[724] |

| Nemesis | Retribution[725] | She is said to have been the daughter of Nyx, and the mother of Helen by Zeus.[726] In the Cypria, this child is born from Zeus violating her while disguised as a swan, following a chase in which she attempts to escape by transforming herself multiple times.[727] She is said to punish those who display hubris or engage in misconduct, and is often equated with Adrasteia.[728] In the 5th century BC, there was a temple to her in Rhamnous, where her cult image is said to have been created.[729] |

| Nike | Victory[730] | In the Theogony, she is the child of Pallas and Styx, and is said to always accompany Zeus.[731] There is evidence of her worship in Magna Graecia, and in Elis from the 6th century BC; she also possessed an altar in Olympia.[732] In Athens, she was intimately linked with Athena, who was sometimes called Nike.[733] In art, she is depicted as a winged figure in mid-flight, wearing draped clothing; one of her best-known representations is the Winged Victory of Samothrace.[734] |

| Nomos | Law[735] | He is first mentioned by Pindar, and is found in works by philosphers. He appears in Orphic literature as the father of Dike or Dikaiosyne, and is addressed in the Orphic Hymns.[736] |

| Oizys | Pain or distress[692] | According to Hesiod, she is one of the offspring of Nyx.[737] |

| Oneiroi | Dreams[738] | Hesiod lists them among the offspring of Nyx, while in the Odyssey they live at the western extremes of the earth. In the Iliad, an individual Oneiros is used by Zeus in his deception of Agamemnon.[739] |

| Palioxis | Rally[740] | In Hesiod's Shield of Heracles, she is depicted on Heracles' shield.[741] |

| Peitharchia | Obedience[742] | According to Aechylus, her daughter is Eupraxia and her husband Soter.[582] |

| Peitho | Persuasion[743] | She is typically found as part of Aphrodite's retinue,[744] and she is sometimes called the daughter of that goddess.[745] In Hesiod's Works and Days, she outfits Pandora with gold jewellry. There is evidence of her cult in Athens, and on Thasos as early as the 5th century BC.[746] |

| Penia | Poverty[747] | In Plato's Symposium, she is the wife of Porus, by whom she becomes the mother of Eros.[748] |

| Penthus | Grief[749] | According to Pseudo-Plutarch, he was not present when Zeus conferred spheres of influence upon the gods, so he was given dominion over honours for (and the mourning of) the dead, the only area which was untaken.[749] |

| Pheme | Rumour or report[750] | According to Pausanias, there was an altar to her in Athens.[751] |

| Philotes | Affection[752] | In the Theogony, she is one of Nyx's offspring.[752] |

| Phobos | Fear[753] | According to Hesiod, he is the son of Ares and Aphrodite, and the brother of Deimos.[754] Alongside his brother, he is said to accompany his father, and to enter into battle in Ares' chariot.[755] He was worshipped in Sparta.[756] |

| Phonoi | Killings[757] | In the Theogony, they are offspring of Eris.[758] |

| Phthonus | Envy[759] | According to Callimachus, he tries to cause envy within Apollo, and in Nonnus's Dionysiaca he concocts a plan to make Hera envious of Semele, leading eventually to the latter's deception. He also appears on a vase from the 4th-century BC.[760] |

| Poine | Vengeance or punishment[761] | She is found alongside the Erinyes, with whom she is assimilated at times.[761] |

| Polemos | War[762] | Pindar calls him the father of Alala, while other sources make him the brother of Enyo or a companion of Ares. He also features in a story from Aristophanes' Peace, where he detains Eirene in a cave.[762] |

| Ponos | Toil and stress[763] | Hesiod lists him among the children of Eris, though elsewhere he is the son of Nyx and Erebus.[763] |

| Porus | Expediency[764] | He is said to be the father of Eros, the husband of Penia, and the son of Metis.[764] |

| Pothos | Erotic desire[765] | He is part of Aphrodite's retinue, and is sometimes said to be her son, or the son of Eros.[765] On vases, he is depicted as a young, winged boy, identical to other figures in Aphrodite's retinue such as Eros and Himeros.[766] |

| Proioxis | Pursuit[740] | In Hesiod's Shield of Heracles, she is one of the figures represented on the shield of Heracles.[767] |